The original recipe comes from Beatrice Ojakangas’ Great Whole Grain Breads. I tweaked it some by replacing the quarter cup of lard or shortening (which I don’t like to use for health reasons) by applesauce and almond oil (I love the taste of apples with molasses and spices, and I like the softness that the oil brings to the dough). I also used dried cranberries instead of raisins (for the added touch of color) and white whole wheat flour instead of regular whole wheat flour (( don’t think white wheat existed at the time the book came out back in the 80’s).

I am still amazed by how docile this dough is, how easily it lets itself be rolled into 36-inch cylinders, how obediently it braids without breaking, how cheerfully it rises and presents its ruddy cheeks to be chiseled into leaves.

I have made it twice so far and twice I have been thoroughly charmed by the sheer pleasure of working it.

The first time I followed Ojakongas’ instruction to brush the top of the leaves and the rims of the wreath with molasses as soon as it came out of the oven. It made it glossy and yummy but on camera, it gave it a burned look (see the picture at the very end of the post) and also it tended to stick to everything (which is a bit annoying if you are going to take that wreath somewhere and need to wrap it).

So the second time, I just lightly floured the wreath before cutting out the leaves and lookswise, I like that version better. Tastewise, it’s slightly less flavorful but on the whole, pretty much a toss.

The loaf is 55% whole wheat.

Ingredients:

For the soaker

- 479 g boiling water

- 100 g dark molasses (not blackstrap)

- 28 g bran

- 53 g wheat germ

- 53 g rolled oats (quick or old-fashioned)

For the dough

- 333 g white whole wheat flour

- 270 g unbleached all-purpose flour

- 70 g gluten

- 40 g unsweetened applesauce

- 16 g almond oil (or neutral oil such as canola)

- 66 g dried cranberies

- 10 g yeast

- 10 g salt

- 1/2 tsp ground ginger

- 1 tsp ground cinnamon

- 1 tsp ground nutmeg

Method:

For the soaker

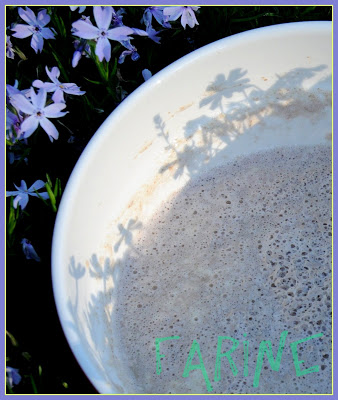

- Put all of the soaker ingredients in a heat-resistant bowl

- Pour the boiling water over them and let soak for 1 to 2 hours (or at least until thoroughly cooled)

For the final dough (I used my bread machine but you can knead by hand or use a stand mixer. In my machine, the wet ingredients go first. In some machines, the dry ones do. So please check your manual for instructions)

- Put all of the soaker in the tub of the bread machine

- Add the oil and the applesauce

- Add the flours, the gluten, the yeast and the salt

- Start the dough program

- When the beep sounds, add the spices and the cranberries. Check to make sure the cranberries are well distributed in the dough. If that’s not the case, take the dough out, knead it by hand for a few minutes and put it back in the machine

- Let the machine run to the end of the dough cycle

- When the cycle has ended, take the dough out of the machine

- Put it on a (very lightly) floured counter and give it as much of a rectangular shape as you can, to make it easier to eyeball it when you next divide it into 3 equal pieces. My dough weighed exactly 1.5 kg, so I knew I had to get 3 x 500 g

- Flatten each of these pieces slightly and shape it into a rough cylinder

- Let rest on the counter under a plastic wrap for about 20 minutes

- Shape each cylinder as you would a baguette (for a baguette shaping photo tutorial, click here) but keep on rolling until you get a 36-inch long rope (it’s best to do it in stages, in other words, to roll out the first one to about 20 inches, then put it back under the plastic sheet and roll the next one, etc. By the time you come back to the first one, it will have slackened some and it’ll be easier to get it to the desired length)

- When you have your three ropes, braid them into a thick plait, then join the ends to make a wreath

- Set on a half-sheet pan covered with parchment paper dusted with semolina

- Put inside a large clear plastic bag to rise. Blow once in the bag before closing it tightly

- Let rise at room temperature about 40 minutes or until noticeably bigger

- Half-way through the rising time, turn on the oven to 375F/191C after placing in it a baking stone and an empty metal pan

- When the dough is ready, dust with flour and use scissors to cut a 2-inch “leaf” by snipping horizontally in each section of the braid; continue to snip leaves all around the wreath; the leaves will lift themselves up as the bread bakes

- Pour 1 cup of water in the hot metal pan, slip the bread into the oven, spray a couple of times and close the door

- After 20 minutes, lower the oven temperature to 350 F/177 C and continue baking for 20 more minutes

- Take out of the oven and let cool on a rack. Enjoy!

Happy Holidays everyone!